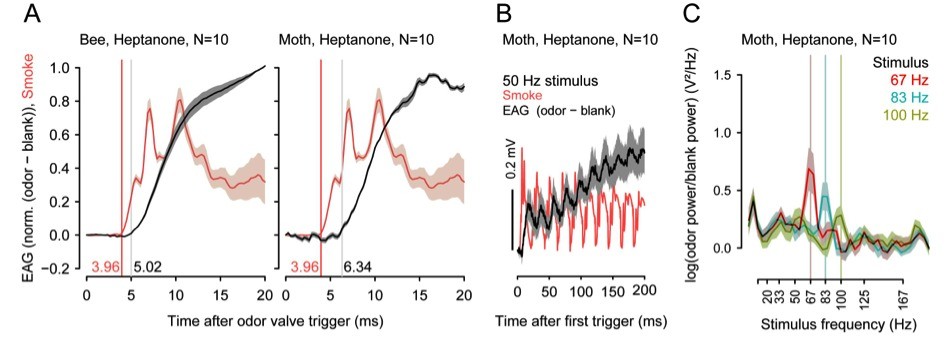

Insects can segregate concurrent odors from closely spaced sources based on short differences in the arrival of odorants. In preliminary experiments with different insect species, we found that odor transduction can occur within 1 to 3ms and odorant fluctuations can be resolved at frequencies above 100 Hz.

Thus, the insect brain could exploit fast stimulus dynamics for odor-background segregation, but how it accomplishes this segregation is not yet known. Moreover, learning modifies odor representations such that relevant odors become more salient, whereas less relevant odors are suppressed. This effect of odor learning might also be used to enhance odor-background segregation by making the AL more sensitive to particular odors.

It is our hypothesis, to be tested with this proposal, that bees use high temporal resolution and odor-learning for odor-background segregation. This allows the animal to create a neural representation of the spatio-temporal structure of the olfactory world. Odorants from the same sources fluctuate synchronously, while odorants from different sources fluctuate asynchronously. Understanding how small and fast fluctuations in relative concentrations of odor mixtures are used by animals to reliably identify odor sources will help us identify common principles of how animals represent and process their environment.